PSE&G

By Steven I. Simon, Ph.D.

Peter A. Cistaro

Implementing Culture Change in any organization with deeply entrenched subcultures presents special challenges. Transforming the safety culture in a utility with dozens of gas, electric and customer service sites requires particularly creative, customized solutions

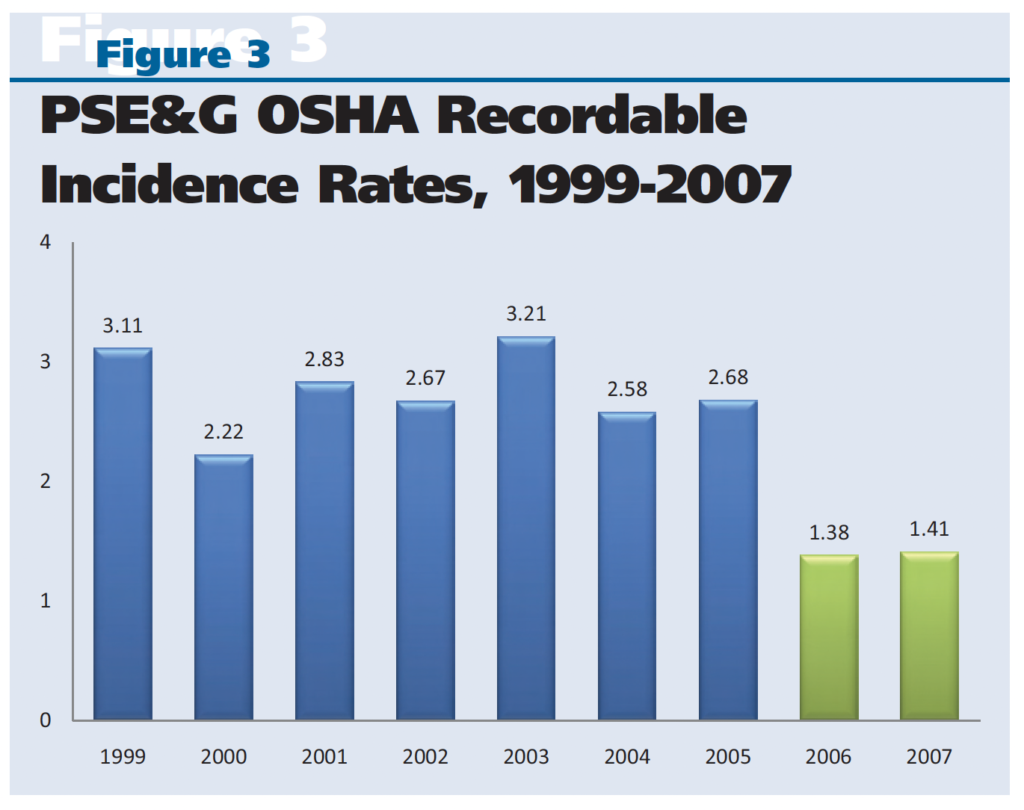

In 1999, New Jersey’s principal utility, Public Service Electric and Gas Co. (PSE&G) embarked on a journey toward safety excellence through culture change. Through this initiative, this organization with 6,500 employees and a record of 32 fatalities in the previous 27 years achieved an OSHA recordable rate of 1.41 and a lost-workday case rate of 0.33 by 2007.

At PSE&G, site-specific subcultures had been in place for generations. Gas delivery was different from electric, north was different from south, urban was different from rural and so on. These different subcultures had different needs. No uniform transformational template—and no cookie-cutter program—could be applied company-wide.

The first phase of the 9-year culture change project made its way through the organization village by village, tribe by tribe, tailoring interventions to fit each individual subculture. The second phase focused on issues that needed to be addressed system-wide—leadership, trust, measurements, learning and communications.

PSE&G recognized that union participation had to be built in from the start. The company committed to enlist grassroots leadership along with management support at every stage, thereby institutionalizing its conviction that culture change could, and should, take place from the bottom up and the top down simultaneously.

The synergy and reciprocity rooted in mutual trust and respect between change agents is key to making long-term culture change journeys work. Peter Cistaro, then the PSE&G vice president in charge of gas distribution and chief internal champion, and Steven Simon, Ph.D., an outside consultant, maintained an open channel over the sometimes rocky terrain of the 9- year journey to create, examine, implement and modify strategy according to shifting conditions. Along the way, dozens of new internal culture change champions joined in, expanding the coalition of leaders at each level of the organization. All involved share the belief that transformation of an organization’s culture is an intensively people-oriented enterprise: it is, after all, people who make it happen. What follows is the story of how the internal and external culture change champions worked together to transform PSE&G’s safety culture.

The Way It Was

In 2003, PSE&G celebrated its 100th anniversary. The company has a proud tradition of providing gas and electric service to its customers. Its employees have a wealth of experience, many of them on the job for their entire adult lives. They are dedicated and hardworking.

For much of the company’s history, the cultural norm was to take some risks in order to get the job done. Jorge Cardenas, manager of the Northern Gas Division, recalls observing a crew opening a 6-ft hole in the road in front of a house in Jersey City to investigate a gas leak. A fire was burning in the hole when the crew uncovered the pipe. It was an extremely dangerous situation. Nearby residents were evacuated from their houses and two inspectors from the New Jersey Board of Utilities were at the scene.

The local crew chief took Cardenas aside and said, “If you can get the inspectors away from here, we’ll jump in there and get the job done, get these people back in their homes.” Cardenas knew the Jersey City guys had a reputation for taking chances and considered getting hurt a badge of honor. Their pride in doing whatever it takes, never mind the risk, explained their 11 OSHA recordables in the previous 6 months. “It hit me right then and there,” Cardenas reports, “that we needed to make some real changes, and we needed to make them pronto.”

In fact, everyone from the chairman on down knew changes were needed. Jersey City was not the only PSE&G district with a poor safety record. The same behavior characterized both the gas and electric sides of the distribution and delivery business throughout the state.

Yet, it was not as though PSE&G had ignored safety. The company had always had at least a semblance of a safety committee system. Safety rules were in place and PPE was readily available. Routine safety audits were performed to monitor the workplace for safety hazards. And there had never been a lack of funds for safety equipment or training. Yet, these programs, taken together, had not been effective because too many people were getting hurt.

Traditionally, safety had been thought of as management’s responsibility, and there were not enough safety-minded managers or safety professionals to go around. Employee involvement in safety was low. Gas and electric delivery are field operations and people are scattered in small crews over 2,600 square miles. Employees in the field tended to do things the way they had been doing them for at least 30 years—bringing problems to management, for example, rather than taking the lead to resolve issues themselves. Each district was its own tribe—and within each resided additional mini-tribes consisting of as few as the two or three workers on a truck crew. A district might have 20 mini-tribes, each doing things according to its own unspoken code.

Despite this, relations between the company and the union had improved as a result of joint effort on quality and legislative initiatives, to the extent that in the late 1990s PSE&G was somewhat fertile ground for seeding a world-class safety culture. Indeed, safety was perhaps the one cause around which all parties could unite. The company’s poor safety performance and recent fatalities provided a clear call to action. All that was needed was effective leadership and a way to make it work.

The Commitment to Change

Change began with an extended benchmark study of companies known for excellent safety programs. Among the salient recommendations produced by the joint union/management benchmarking team was a new safety system, creating a safety constitution and a safety congress for the company.

The new system incorporated 19 component mandates representing key aspects of safety from accountability to training, which were manualized and scheduled for serial implementation companywide over a 5-year period. Development of a new safety structure for managing the safety program was one critical mandate.

The safety structure was to operate on two levels. A local safety council (LSC) made up of represented workers, managers, supervisors and SH&E professionals, was to be formed for each district and division. A separate line of business council (LOB)was to be formed for gas, electric and customer operations, the membership of each to be comprised of the LSC chairpersons and the respective LOB upper management. Of particular importance, chairpersons in all cases were to be drawn from the grassroots—frontline, bargaining unit workers (Figure 1, p. 30).

This new structure dedicated significant people resources to safety. It emphasized the commitment to full engagement of frontline employees in the safety process: the LSCs were designed to foster much greater grassroots responsibility for their own safety. The structurevwas based on the recognition that creating a positive safety culture requires involvement and engagement by all levels of the organization. It set the stage for the shift from a command-and-control approach to managing safety to a hybrid approach that is grassroots led and management supported.

Skepticismsurfaced overwhether the newsystem and structure would amount to just another flavorof- the-month tactic, but because the unions had been accorded a share in leadership, hopes were high that the commitment was real this time. In fact, senior managers and top union officials signed a safety commitment statement (Figure 2, p. 31). It was writ large and posted across the utility tomake their commitment to an accident-free workplace known to all.

Enter Culture

By 1999, 2 years had passed and the new safety systemand structure were being put in place. Cistaro was trying to develop increased employee involvement in safety, which he saw as a potential anchor strategy for improvements in other areas and in which he maintained a key personal interest. Building on the fact that represented workers at PSE&G were becoming increasingly responsive when it came to safety issues, Cistaro brought some LSC chairpersons to the annual meeting of the New Jersey State Safety Council, of which he was then chair, to see whether they might return with some good ideas.

The union chairpersons spread out at the meeting, but two of them quickly corralled Cistaro and hurried him to a talk on achieving a world-class safety culture. “You have to get over here and listen to this guy. He might as well be talking about us.” The speaker was Steven Simon, and Cistaro was struck by how well his examples embodied where PSE&G was and where it wanted to go.

Simon asserted that safety excellence is a product not only of the right programs, such as the safety system PSE&G had just designed and adopted, but also of the right culture. He compared the two factors to a stew and its broth. Safety programs are the ingredients in the stew—policies, systems and processes as the meat and vegetables, while the prevailing culture is the broth. If the ingredients are cooking in a wholesome broth—a positive safety culture of trust, caring, responsible leadership—everything works to its potential: incident investigations are open and honest, root causes are identified and countermeasures are easily designed; and training iswell-attended and productive. However, if those safety programs are swimming in a rancid broth—a safety culture characterized by mistrust, poor communication, lack of leadership—the stew will be ruined: incident investigations will be marred by suspicion, prevarication and withholding; root causes will remain elusive and countermeasures a matter of guesswork; and training will be poorly attended and unproductive.

In PSE&G’s case, all 19 components of the new safety system would flourish only in a wholesome broth. That was a revelation to the PSE&G union representatives and it became clear to them that only part of the journey toward safety excellence was in fact underway. Introduction of the new system and structure had created a scaffolding for safety improvement at PSE&G, but values, norms and behaviors had a long way to go.

Cistaro recognized that culture change might fill the gap he knew existed at PSE&G. He invited Simon to address the nextmonthly LBC safetymeeting, where Simon asserted that now culture needed as much attention as programs had received. He introduced the importance of enlisting leadership at all levels of the organization, of working on safety culture by means of a grassroots-led, managementsupported approach.

Phase 1: Culture Change Village by Village, 1999-2003

Crafting the Strategy

The next step was devising the right roadmap for intervening at PSE&G. The approach needed to make sense in terms of the geographic dispersal of the gas and electric locations aswell as in terms of the history, existing culture and current needs of each. In 1999, the utility had four electric divisions with 400 to 500 constituents apiece, and 11 gas and appliance services districts of about 150 people each. Customer operations (meter readers) were a separate department of 1,200. How does one get one’s arms around that?Where does one begin culture change? Initially, Cistaro advocated for a roadmap that landed at every site in the company— in other words, for a utility-wide initiative. After all, if culture change was worth doing, it was worth putting in place everywhere

An employee-led safety council structure was one of the key components of the new safety and health system. Those asked to serve as chairs responded with enthusiasm, yet most had no experience chairing a committee. The chairperson training program was designed to teach the basics:

- How to Move through an agenda and keep notes

- Facilitate open discussion

- Resolve issues and communicate the resolutions.

The next step was devising the right roadmap for intervening at PSE&G. The approach needed to make sense in terms of the geographic dispersal of the gas and electric locations as well as in terms of the history, existing culture and current needs of each. In 1999, the utility had four electric divisions with 400 to 500 constituents apiece, and 11 gas and appliance services districts of about 150 people each. Customer operations (meter readers) were a separate department of 1,200.

How does one get one’s arms around that? Where does one begin culture change?

Initially, Cistaro advocated for a roadmap that landed at every site in the company— in other words, for a utility-wide initiative. After all, if culture change was worth doing, it was worth putting in place everywhere care and on a fast track. In fact, many companies adopt such an approach. However, the culture was not uniform across the sites, so the interventions could not be applied uniformly either.

An optimally sustainable transformation would proceed village by village. It would identify and honor the particular strengths, needs and resources of each individual culture. Furthermore, global lessons learned in one area could be applied to the next, facilitating course corrections. When it was agreed that this approach offered a better platform for culture change, two pilot locations were selected.

The next critical question was who would drive the change process. It is important to tailor the intervention to fit an organization’s existing structure. Since PSE&G’s safety structure emphasized that safety was to be driven from the grassroots level, the culture change process should be driven from the grassroots as well.

However, because culture change driven by the grassroots cannot realistically succeed without management support, it would be vital to enlist and educate safety culture leaders from both constituencies within each location. To produce a sustainable new safety culture, parallel paths for change would have to be put in place among represented workers and through the existing management system—within each village and within the company as a whole.

Pilot Interventions: Different Strokes

The first phase of the culture journey at PSE&G took place from 1999 to 2003. The two pilot locations became demonstration projects to show people what the process was like, gaining buy-in from both union and management, and spreading the word in advance of a larger roll-out. One pilot program was launched at New Brunswick Gas, which had a strong safety record and a good working relationship between union and management, and the other in the Central Electric Division, where injuries and controversy were more common.

It was decided that New Brunswick was ready to begin implementing culture change with a traditional sequence whose first step was an assessment. That would enable the site to seewhere itwas so those involved could determine where they wanted to go. To generate baseline quantitative data about the culture, all employees participated in a safety culture perception survey; the data were amplified, qualified and textured through focus groups and interviews. The results, complete with recommendations, were reported to a joint group of union and management personnel during a 2-day feedback session that offered a careful snapshot of the division’s culture, then invited participants to define key issues and brainstorm interventions that would best advance them in a more positive direction.

In 1999, the Central Electric Division had too many unresolved union and management issues to take the conventional culture assessment route. Mistrust and suspicion were rampant. Stories were told about workers who reported phantom injuries to get management in trouble and about managers who disciplined first and investigated later. Before the factions could unite around a commitment to assess the safety culture— much less around actions to improve it—they needed to address the longstanding mistrust that undermined every interaction between union and management at this location.

In keeping with the philosophy of tailoring intervention to need, the first step was to host a 3-day workshop that brought together 30 key leaders from the ranks of union and management and created an opportunity for them to identify the underlying assumptions which fueled mistrust, disrespect and negativity in their relationships and, in turn, spawned a poor safety culture. The facilitated exchange of perceptions and working through of the issues voiced over the course of the workshop produced positive results in the form of action plans for the short- and long-term future as well as praise for their counterparts by management and union leadership— a definite leap forward.

In retrospect, starting with two different pilot projects served this initiative well. Launching the process with an assessment in a highly successful location produced a template that would be modeled by other successful sites; in fact, it has since been applied in five more gas locations and one electric location, as well as in the transportation and materials management departments.

Likewise, initiating the process by intervening where an adversarial relationship prevailed between workgroups established a model for galvanizing partnership in the face of union/management unreadiness to work together. The 3-day workshop has proved to be so powerful a tool that eight more sessions have been instituted since 2000.

Enlisting Senior Managers as Leaders

At the launch of the pilot projects, Cistaro, aware of the effect of strong leadership on safety performance, asked Simon to meet with his management team. He recognized that empowering and unleashing the grassroots to exercise leadership for safety without preparing management to respond to the increased safety emphasis could derail the entire process. Consistent with the decision to drive the culture change journey from both the top down and the bottom up, Cistaro sought to develop the skills of his senior leadership team—his direct reports in charge of the gas and electric businesses— toward advancing their transformation into effective safety culture leaders.

Several members of this team initially showed resistance to the initiative. They felt they were spending more time than ever on safety—perhaps too much time. The new 19-component safety system made for a lot of work, as did the monthly LSC meetings and the monthly all-day LBC meetings. But Cistaro believed this team had to learn to support the culture change process as it was rolled out in their divisions and districts so they could encourage and harness the participation of their field personnel.

A self-assessment survey provides a vehicle for leaders at all levels of the organization to evaluate their current safety culture leadership skills and develop action plans to improve them. At PSE&G, a 25-item instrument was used to assesses strengths and weaknesses around five key leadership practices.

Examples Follow:

- Making the case for change: “I successfully communicate to people in our

organization how improvements in the safety culture benefit everyone’s longterm

interests.” - Shared vision: “I talk about the kind of safety culture we want to create together.”

- Building trust: “My actions are consistent with the values I espouse.”

- Developing capability: “I consistently seek to develop the skills and knowledge in myself and others to meet the challenges of changing the culture.”

- Recognition: “I make sure that people who contribute to success receive recognition.”

The next step was devising the right roadmap for intervening at PSE&G. The approach needed to make sense in terms of the geographic dispersal of the gas and electric locations as well as in terms of the history, existing culture and current needs of each. In 1999, the utility had four electric divisions with 400 to 500 constituents apiece, and 11 gas and appliance services districts of about 150 people each. Customer operations (meter readers) were a separate department of 1,200.

How does one get one’s arms around that? Where does one begin culture change?

It was recognized that senior managers’ time and attention had been taken up managing—rather than leading— the safety program. It was in that context that safety culture leadership became a priority. From the early stages of the undertaking, senior managers were educated to lead the journey, supervisors received intensive leadership training, and safety culture transition teams would be established to guide and sustain the process, reflecting the hybrid structure.

When members of this team were asked to define their individual roles as leaders in the organization with regard to safety (“What are you doing personally?”), many indicated they sponsored mandated safety meetings, audits and training by coordinators. These were not the desired answers. It was not enough to have a great institutional safety program. Safety had to be practiced by everyone, particularly leaders, every day. They had to focus people’s attention on safety issues—they had to set the example.

- The first initiative developed by the leadership sub-team was to increase the number of individual grassroots safety champions. It was pursued through mentoring and peer-to-peer coaching. Success was realized when the first group of chairpersons rotated.

- The second leadership initiative was to develop the safety culture leadership quotient of middle management. It was aimed at addressing a significant change brought about by the adoption of the new safety and health system in 1997, namely that whereas the old safety system was supervisor-led, the new system was employeeled. Many supervisors, who traditionally handled the safety programs, were out of sorts in dealing with a supportive role in safety rather than a leadership role. The second initiative provided sequential workshops that helped supervisors develop a better understanding of their new role through developing the safety culture leadership skills of middle management. The result was their greater engagement in the safety process.

- The third leadership initiative was to improve the relationship between street leaders and supervisors in the gas department. In addition to learning to speak the language of culture and the corresponding tools, the sessions helped develop the street leaders’ capabilities to walk the delicate balance between supervising a crew of union workers and being safety leaders. The key result of these sessions was more people returning home safely each day. Their success could also be seen in greater participation in the local safety council structure and the increase in near-hit reporting.

To that end, members of the leadership team completed a safety culture leadership inventory, compiling a list of their individual and collective leadership skills. Members committed to use their influence as leaders in their divisions to cultivate their home ground so that when the culture seed was planted, it would have a greater chance to germinate and grow. Each division was promised that it would receive at least one project of its own.

The momentum for enlisting leadership cascaded down to the next level even as the division managers continued to meet bimonthly with Cistaro and Simon. Their chief subordinates attended a 3-day off-site course designed to develop safety culture change leaders. By now the number of people with the body of knowledge to champion a safety culture change initiative at the utility has grown to a critical mass.

Enlisting Supervisors as Leaders

The members of the senior leadership team represented only a small part of the PSE&G management structure. Frontline supervisors actually had the most interaction with the grassroots. Jorge Cardenas, the Northern Gas Division manager mentioned earlier, identified a need and personally drove an effort to provide the supervisors in his territory with the means to effect change.

He came up with a plan that would spread culture change throughout his five districts, each with 150 employees, even before they got their promised individual projects. His 75 managers and supervisors met once every 4 months and devoted half a day to training in the tools and methodology for changing the safety culture. The initiative to create leaders at the supervisory level was so well targeted that it was adopted by nearly every electric and gas location in the company.

Again, like the safety culture assessment and the breaking cycles workshop in the pilots, an intervention tailored to address the need of a particular village resonated and was eventually replicated throughout the entire organization.

Devising a Guiding Coalition for Each Village

A long-term process like safety culture change needs not only the templates established locally but also a sturdy superstructure under which key leaders can manage the transition from the prevailing safety culture to the safety culture of the future. To accomplish this across a division, the first safety culture transition team (SCTT) was set up in the Palisades division, on the electric side of the business.

It was December 2000 and Palisades had experienced a particularly bad year. The existing safety committee structure was not advancing the necessary change. A parallel team that focused exclusively on culture issues had to be created. Cistaro and Simon agreed on a dedicated group comprised of union and management leaders, all of whom committed themselves to the transition team. In fact, they have been meeting for 4 hours every other week for more than 7 years, and their efforts have created a turnaround in the division. Both Cistaro and the head of the union, who attended the early sessions regularly, share the conviction that these meetings have produced some of the most open and fruitful discussions that they have ever engaged in. By this time, it was almost axiomatic that the success of a trial initiative would spread throughout the organization—and it did. Soon, every electric division had its own SCTT.

Phase 2: Culture Change Utility-Wide, 2003-2007

After 4 years of establishing the elements to sustain the safety culture change journey in PSE&G’s separate business units and their divisions and locations, it became apparent that some issues essential to continued success would only be resolved through utility-wide initiatives and support. The catalyst for embracing a utility-wide focus was the observation of new president Ralph Izzo in 2003. He noted that while tremendous improvement had been achieved since the creation and adoption of the new safety system in 1997, the OSHA recordable rate had reached 3.21—and stayed there. “Can we break through this plateau?” he asked his senior leadership team. “What do we need to do to get to the next level?”

The response reflected his team’s conclusion that since the company’s safety programs were fine, the margin for improvement resided in attention to the culture in which they were implemented. Izzo questioned his team intently until he came to understand and share their vision of the link between enhancing the organization’s safety culture and achieving a breakthrough in OSHA rates. He assumed the necessary leadership role and within a short time articulated his own vision of a safety culture to his executive team and union leaders.

Izzo,who came inwith a reputation as a numbersoriented manager, said he would gauge progress not only by quantitative measures but also through the quality of safety dialogue. As a kind of a one-man focus group, he collected impressions by listening to people at all levels of the company. His embrace of a subjective metric was not lost on those who worked for him. It reflected his evolving respect for the importance of the people side of safety and paved the way for skeptics—on his executive team, in the supervisory ranks and in the union—to unify their efforts toward working on the culture.

Creating a Utility-Wide Vision

- Measurement and benchmarking

- Communication;

- Trust

- Leadership

- Learning and knowledge sharing

- Identifying what is missing.

Launching the Utility-Wide Safety Culture Transition Team

- The Measurements & Benchmarking subteam created a new system of leading indicators to replace the focus on OSHA recordables as the sole measurement; called SLIM (Safety Leading Indicators Measurement), it looks at upstream activities that are intended to produce improved safety performance (see above).

- Shared vision: The Leadership subteam identified three initiatives:

- to expand the base of individual grassroots safety champions;

- to develop the safety culture leadership quotient of middle management; and

- to improve the relationship between street leaders and supervisors in the gas department

- The Communications subteam created a popular training program that taught skills for the many rank-and-file people who had limited experience chairing the local safety councils.

- The Learning & Knowledge subteam created an intranet site for coordinating all safety information.

- The Safe Driving subteam crafted a safe driving component that was added to the safety and health program (see the web extras).

- The Ergonomics subteam initiated efforts in job safety analysis.

The utility-wide SCTT was launched in December 2003 with 15 members. Forty-five additional leaders from union and management ranks across the organization were invited to choose which of the six safety culture subteams they wanted to join. Then, beginning in January 2004, each subteam assembled to create and, upon approval from the SCTT, detail an initiative to address its assigned safety culture imperative.

The documented work plans identified the deliverable, the team member responsible, the key milestones, the desired accomplishment and results, and the completion status. Once ratified by the SCTT, the subteams’ work plans became major company-wide initiatives for deployment by the separate LBCs across the utility (see sidebar on p. 34). This highly structured process served the needs of both the subteams and senior management, institutionalizing a method by which teams could garner support for the solutions they designed for their defined problems and senior management could tap into each initiative’s objectives and resources up front before committing to implementation.

The corporate SCTT met monthly to make decisions around the subteams’ initiatives; to eliminate roadblocks and supply the resources necessary for the effective implementation of their work plans; to work with the management sponsors and team leaders; and to keep communication about the initiatives flowing throughout the organization. The SCTTwas given the authority to determine when subteams have run their course or when they should be renewed and given the wherewithal to rejuvenate themselves.

Key Take-Aways from the PSE&G Experience

Culture change is a long-term process. PSE&G’s 9-year project was predicated on the organization’s internalization of the importance of the following:

- Look beyond safety programs to the surrounding culture.

- Develop authentic partnership for change between internal champions and outside consultant, building on trust and synergy to craft strategy and interventions.

- Recognize that interventions must be tailored to address the culture or subculture in question rather than be developed and implemented in a cookie-cutter manner.

- Engage and empower union employees from the start to provide genuine grassroots leadership.

- Enlist and maintain strong, consistent support for that leadership from management.

- Respond to emerging realities both village by village and organization-wide by improvising design accordingly instead of adhering to prepackaged strategies.

Conclusion

The first phase of the PSE&G safety culture change journey wound its way around this major utility village by village. The second phase focused on issues that could only be addressed system-wide. Throughout the process, a hybrid approach that enlisted grassroots leadership and management support was adopted.

The outcome has been the creation of an authentic, sustained safety culture. Walk into any PSE&G location these days and one will hear the language of culture. It permeates the organization. Discussions about safety have moved beyond talk about engineering or training fixes to norms, perceptions, values, beliefs and behaviors. There are safety culture leaders at all levels of the organization, walking the talk.

- Participation: monthly safety meetings (percent attendance and quality); near misses; stop the jobs.

- Inspections: completing guideline of eight inspections per month; issues resolved.

- Training: percentage of people completing safety training.

- Jobsite observations: number JSOs completed; percent safe behaviors; completing corrective actions.

Implementing Culture Change in any organization with deeply entrenched subcultures presents special challenges. Transforming the safety culture in a utility with dozens of gas, electric and customer service sites requires particularly creative, customized solutions.

As Published In:

American Society of Safety Professionals

References

To view several additional items related to this article, visit www.asse.org/psextras.

Hogan, R. & Kaiser, R.B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 169-180.

Kotter, J.P. & Heskett, J.L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: The Free Press.

Ryan, K.K. & Oestreich, D.K. (1998). Driving fear out of the workplace: Creating the high-trust, high-performance organization (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schein, E.H. (1983, Summer). The role of the founder in the creation of organizational culture. Organizational Dynamics, 13-28.

Schein, E.H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schneider,W.E. (1995). Productivity improvement through cultural focus. Consulting Psychology: Practice and Research, 47(1), 3-27.

Simon, S.I. (1998). Safety culture assessment as a transformative process. Proceedings of the ASSE Behavioral Safety Symposium, USA, 192-207.

Simon, S.I. (2001). Implementing culture change: Three strategies. Proceedings of the 2001 Behavioral Safety Symposium: The Next Step, USA, 135-140.

Zohar, D. & Luria, G. (2005). Amultilevel model of safety climate: Cross-level relationship between organization and grouplevel climates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 616-628.