Lawrence Livermore National Labs

This is a story of synergy: it’s about what can happen when leaders, grassroots teams and consultants trust each other to get a job done. It’s about partnership. It’s about a motivated group of crafts people who led a grassroots effort to make their jobs safer. It’s about the role leadership played in sustaining that movement over time. It is also the story of how one, dedicated plant engineering manager broke new ground to achieve success

Change from the Bottom-Up, with Management Support

There are three approaches to changing a culture, and this is true whether you are working on safety, quality, trust, communication, or any other aspect of the culture. You can use a topdown approach, bottom-up, or a combination of the two. There is no ‘best way.’ Each has its advantages and disadvantages, and any can produce good results. Our experience is that it is best not to use an approach that runs contrary to the existing management style.

At LLNL, the impetus for culture change started with management and quickly caught fire in the grassroots. Before starting on the grassroots safety culture journey, notwithstanding a strong, traditional safety program, the safety record of the lab was less than stellar; with a disproportionate number of those accidents affecting the approximately 500 workers in the Maintenance & Operations (M&O) division of the Plant Engineering Department—those skilled and semi-skilled workers who encounter unique and varying conditions, as well as hazards, daily.

We had been working for a few months with Department management and supervisors on adding a cultural component to their safety program. After only a few sessions, Bernie Mattimore, who was then chief of the M&O division, became a strong advocate for our approach focusing on the ‘culture’ of safety. He was to admit, I realized that for 25 to 30 years, however long I had been in this field, I had been concentrating on the wrong things when it came to safety. I had been working exclusively on correcting unsafe conditions, without giving much thought to unsafe acts.”

Bernie was determined to correct course. He invited Culture Change Consultants to present to the M&O Executive Safety Committee (ESC), to explain the concept of safety culture change, and to share some of the principles of the CCC methodology. We outlined the connection between organizational culture and behavior, and we explained the need to get more workers actively involved in the safety process, to build a more participatory safety culture. It seemed to strike a chord with many in the room. They were an experienced group, many of whom had been working on the ESC for years and had grown increasingly frustrated with the recent lack of progress.

After considerable back and forth, the membership decided to transform the committee into a grassroots-led team. The team, primarily focused on safety culture, was made up almost entirely of hourly workers, with one non-voting member of management. There was some initial resistance and suspicion on the part of workers, but ultimately labor leadership was persuasive in convincing its members to give this new initiative a change.

Management support for the proposal, on the other hand, was almost instantaneous. Bernie Mattimore was predisposed to the plan and his boss, Jan Cook, was willing to let Bernie go out on a limb. Making that limb a little shakier for Bernie, Jan was designated as the non-voting member of the newly-formed Grassroots Safety Committee (GSC), privy to all its workings and available to hear any feedback about the M&O chief.

Lesson One: Letting Go is Hard to Do

Bernie Mattimore would appear from his resume to be an unlikely culture change hero. Trained as an engineer and having served in the U.S. Navy, he had concentrated on physical fixes of visible problems for the entirety of his career. He did not exactly fit the profile of a manager who would surrender a good measure of control over his safety program to a grassroots assemblage of hourly workers focused on culture. Several managers were skeptical. But Bernie thought it was the right thing to do. “Who has more at stake than the people who do the work?” he reasoned. “Who knows the job better? Who better to change the culture of the group than the group members themselves?” Most managers would acknowledge the wisdom of that point of view, but it takes exceptional leadership to follow through, to let go of the reins, and to give the workers much of the power over the safety program. “And I made sure they knew that with empowerment comes responsibility,” says Bernie.

Bernie relied on the committee to succeed and to justify his faith in them, and they were relying on him for support. “Suddenly, you find yourself in a life raft with all these other people and if you’re not all pulling together, in one direction, you may not survive. And you are no longer the captain, just another shipwrecked survivor. And they know more about rafts and rowing than you do. It takes a lot of trust, but it’s the right thing to do.”

“Who better to change the culture of the group than the group members themselves?”

Lesson Two: Building Trust

Among the many ingredients that comprise an organization’s culture, Bernie says that trust is the most important. “Basically, you have to do what you say you’re going to do. At the same time, you have to extend trust, believing that others can and will do what they say.”

An early experience helped establish a good measure of that trust. There had been a fairly serious accident involving a machine guard. Lab upper management ordered that work on all cutting and grinding machines be suspended until they could conduct a complete review. Despite the pressure to get back on-line, Bernie thought this might be an appropriate task for the Grassroots Safety Committee to undertake – on their own. On a Friday, they accepted the challenge. On Monday afternoon, they reported back to Bernie, having looked at all the machines, talked to all the appropriate people, and figured out solutions for what needed fixing.

For trust to grow, and the culture to mature, Bernie had to take them at their word. He gave them his vote of confidence. That afternoon, he reported to upper management that the review was complete. When management notified him that an inspection by a DOE Tiger Team was pending, he confirmed that they were ready for it. They started up operations again and a few weeks later, as promised, the Tiger Team inspectors arrived. The Tiger Team inspector was so impressed that they recommended the Grassroots Committee offer its services to other departments at the Lab, to help them review their machine safety guards.

Bernie was relieved and gratified that his placing trust in the “grassroots” had proven to be justified. The Grassroots Committee, in turn, learned that management was sincerely committed to managing safety in a new way, with greater worker involvement, independence and responsibility.

Lesson Three: Leadership at all Levels

At Culture Change Consultants, we have amassed a considerable amount of knowledge about the factors that enable change, and we, like others, often talk about leadership as being the most important. While it is management’s function to manage the business, to meet production goals, hit deadlines, and ensure quality standards, it is leadership’s role to manage the change process. Sometimes, as in the M&O department at LLNL, an organization is fortunate to have, among the management team, a person who can also function as a champion and change leader.

Bernie had the advantage of support from his boss. He also found, among the members of the Grassroots Safety Committee, a number of natural leaders willing to take up the cause. The M&O division was blessed with strong, experienced and charismatic leadership throughout its workforce. They proved eager to help blaze a new trail and to bring along their sometimes reluctant, often skeptical, and occasionally critical constituency.

“Without the leadership of these outstanding individuals, we wouldn’t have gotten anywhere,” says Bernie. “They were willing to work hard, take risks, and sometimes withstand the brickbats of their peers. Nobody likes to be called a company stooge, but these guys knew better and were willing to stick their necks out.”

In our work, we also talk about transformational leadership as being essential to bringing about a culture change. By that, we mean leaders who are willing to leave their comfort zone and try new approaches. These are people who say to themselves, “This is not working, too many people are getting hurt; we need to try something different.” Transformational leaders also have the capacity to do something even harder, to look in the mirror, see their own flaws and shortcomings, and be willing to change themselves.

LLNL embraced and applied what we taught about transformational leadership, and in turn, we took home lessons from Bernie, who proved to be the quintessential transformational leader.

Transformational Leaders are leaders who are willing to leave their comfort zone and try new approaches

Lesson Four: Taking the Time to Garner Support

The grassroots “revolution,” as it came to be known, was new territory for everyone: for Bernie, his bosses, the Grassroots Safety Committee, and the Department of Energy. They were navigating new terrain, but with the promise of reward. Enthusiasm was high. The GSC was revitalized, and effective new safety programs were initiated.

Lesson Five: Engaging Employees to Complete Culture-Based Projects

Improving an organization’s safety culture requires work in two areas simultaneously, on culture issues such as responsibility, trust, and communication, as well as on real, achievable safety projects. At some facilities, this requires a careful balancing act as there may already be traditional safety committees carrying out projects. In that case, it is essential for grassroots teams not to cross boundaries but rather to concentrate on complementary cultural projects.

We have done assessments at hundreds of facilities. Focus group comments inevitably reveal worker knowledge of unsafe conditions that may go years, or until an accident, before being fixed. Much of the time, these are fixes that could be performed by the workers themselves without the intervention of management, engineering, or specialized maintenance. But, so often at such facilities, we hear, “that’s just not the way things are done around here.”

Bernie made it clear early on that the shift of responsibility would not be one of convenience, with the GSC cherry-picking projects. For him, the real work was in the execution and the follow-through.

One of the long-standing issues at the Lab was the question of worker safety with regard to exhaust fumes while working on rooftops. The GSC proposed the development of a permit process to ensure that, prior to starting a job, either a particular roof was certified as safe or the workers would be given all necessary safety equipment and procedures. Bernie thought this was an important project and appointed Jerry, an air-conditioning mechanic who served as the chair of the GSC, to take his place on the plant wide Lab Safety Council to sell the idea and secure their support.

It was a good experience for Jerry and the others, Bernie says. “He was able to understand the difficulties and frustrations of the middle manager. Let’s face it, everybody has a boss. Everybody has a budget. People are competing for resources and attention. Before, the perception had been, ‘Bernie doesn’t want to do it.’ If you explained, it was just smoke and excuses. Now, Jerry and the others could understand some of the complications. Eventually they learned how to work the system. In many cases, they did it better than I did.”

Jerry and the GSC were able to ‘walk a mile in Bernie’s shoes.’ And, while it wasn’t easy, they worked within the system to refine and develop a method to ensure rooftop safety. That method is still practiced throughout the Lab and has been copied by other DOE facilities and companies.

Lesson Six: Although it is Important to Focus on the Process, Early Successes and Good Numbers Can Help Promote Your Agenda

The grassroots “revolution,” as it came to be known, was new territory for everyone: for Bernie, his bosses, the Grassroots Safety Committee, and the Department of Energy. They were navigating new terrain, but with the promise of reward. Enthusiasm was high. The GSC was revitalized, and effective new safety programs were initiated.

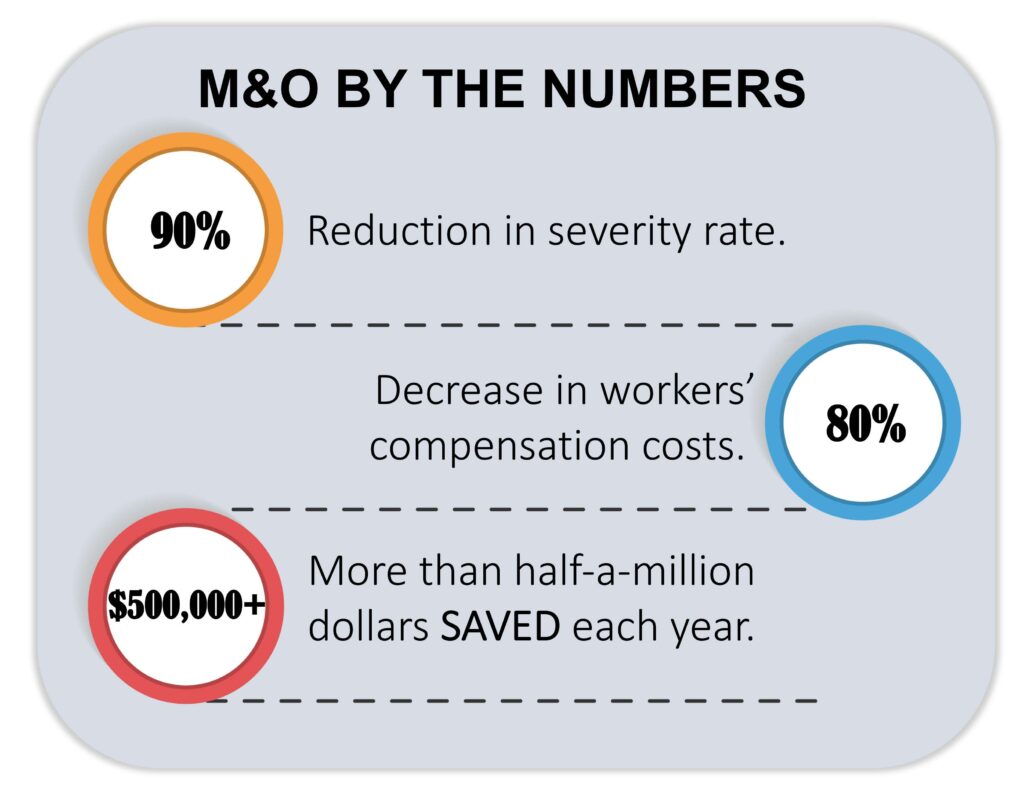

According to Bernie, “It was clear that we were on the right track. All you had to do was walk around the shops or attend a meeting of the GSC to see that safety and overall morale were improving. That’s what we were focusing on, but you know how managers are, they like to have their numbers.”

The numbers supported what observation and intuition suspected. By the third year of the process, accident rates in the M&O department had been markedly reduced, with a decline in lost workdays from 455 to 265 and in restricted workdays from 372 to 42, and workers’ compensation costs were down 80%, a savings of more than half-a-million dollars a year. Although they had been advised not to put much stock in numbers, particularly lagging indicators such as incident rates and recordables, it was an encouraging trend.

These excellent results did not go unnoticed. When Tara O’Toole, the Department of Energy’s top ESH officer, came to Lawrence Livermore on one of her periodic site visits, she requested a meeting with a group of employees involved with safety. Management steered her directly to the M&O’s Grassroots Safety Committee.

Accompanied by the top brass at the lab, O’Toole set out for the meeting. At the door, she turned back her entourage, requesting that no members of management be present. What the managers expected to last 15 minutes went on for an hour and a half, while they paced the floor with rising anxiety. But they had no cause for concern; O’Toole was extremely impressed with the grassroots safety leadership process that the GSC had developed. She was so impressed, in fact, that she suggested that the all-employee safety committee host a conference for representatives from other DOE sites, to help promote additional grassroots driven initiatives.

Lesson Six: Although it is Important to Focus on the Process, Early Successes and Good Numbers Can Help Promote Your Agenda

The grassroots “revolution,” as it came to be known, was new territory for everyone: for Bernie, his bosses, the Grassroots Safety Committee, and the Department of Energy. They were navigating new terrain, but with the promise of reward. Enthusiasm was high. The GSC was revitalized, and effective new safety programs were initiated.

According to Bernie, “It was clear that we were on the right track. All you had to do was walk around the shops or attend a meeting of the GSC to see that safety and overall morale were improving. That’s what we were focusing on, but you know how managers are, they like to have their numbers.”

The numbers supported what observation and intuition suspected. By the third year of the process, accident rates in the M&O department had been markedly reduced, with a decline in lost workdays from 455 to 265 and in restricted workdays from 372 to 42, and workers’ compensation costs were down 80%, a savings of more than half-a-million dollars a year. Although they had been advised not to put much stock in numbers, particularly lagging indicators such as incident rates and recordables, it was an encouraging trend.

These excellent results did not go unnoticed. When Tara O’Toole, the Department of Energy’s top ESH officer, came to Lawrence Livermore on one of her periodic site visits, she requested a meeting with a group of employees involved with safety. Management steered her directly to the M&O’s Grassroots Safety Committee.

Accompanied by the top brass at the lab, O’Toole set out for the meeting. At the door, she turned back her entourage, requesting that no members of management be present. What the managers expected to last 15 minutes went on for an hour and a half, while they paced the floor with rising anxiety. But they had no cause for concern; O’Toole was extremely impressed with the grassroots safety leadership process that the GSC had developed. She was so impressed, in fact, that she suggested that the all-employee safety committee host a conference for representatives from other DOE sites, to help promote additional grassrootsdriven initiatives.

Lesson Seven: If You Are a Change Leader, Be Prepared to do Things You’ve Never Done Before - Way, Way Out of Your Comfort Zone

When management learned about O’Toole’s suggestion for hosting a conference, they immediately encouraged the grassroots committee to go ahead and give it a try — even though they had no experience in event planning. And the committee readily agreed to accept responsibility for the event.

“You could say that management developed a lot of confidence in the grassroots and that the committee had developed a lot of confidence in its own abilities,” Bernie said. “You could also say that we were all pretty naïve, with no idea of the challenges ahead.”

And so it was that a group of hourly workers: welders, electricians, custodians, etc. developed a conference for DOE managers, safety professionals, and fellow workers from across the country. From scratch, they created “The First Safety Culture Revolution Through Employee Empowerment Workshop,” sponsored by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Energy Facility Contractors Group (EFCOG). Initially, they envisioned a mini-conference, with about 50 attendees, but the response was so positive they had to cap attendance at 120. In addition to DOE facilities, there were representatives from more than 10 U.S. and Canadian companies.

The format of the conference reflected their participatory philosophy and the approach paid off. Attendees were anxious to brainstorm a number of topics, such as: envisioning a safety culture, delineating the driving forces for change, identifying barriers to change, and approaches to building teamwork.

“To say it was a success would be an understatement,” Bernie says. “The positive response was overwhelming. I can’t say enough about the 30 committee members who made it happen. Participants were ready to sign up for the next conference and we thought we were just doing the one!”

The conference did, by popular acclaim, become an annual event. In spite of the tremendous amount of work involved, the grassroots safety committee agreed to remain as organizer. Having become logistics experts and polished public speakers, they became chairs of the event, which continued annually for eight years.

Lesson Eight: It’s Easy to Lose Focus, so Take Measures to Maintain Momentum

For many years, the grassroots safety process performed admirably. Gradually, however, energy and enthusiasm began its natural decline. “What had been a great safety program when we started, was merely good seven years later,” says Bernie. “Everybody knew it. The great thing is, the workers recognized it and wanted to do something about it. At that year’s EFCOG conference, they stood up and said, ‘We have a problem and we’re not sure what it is.’ And they really opened up during the conference and looked hard in the proverbial mirror.”

According to their critical self-analysis, there were a number of factors that contributed to the decline of the effectiveness of the GSC.

One of the changes was that, for the first time in decades, LLNL had to bid for their contract. There was a lot of anxiety, and fear that people may lose jobs, benefits, and their excellent retirement packages. People feared the bidding out of all the crafts work. There was more pressure than ever to reduce costs. The message was clear: if your group cannot be more cost effective than outside people, the work will be contracted out and jobs will disappear.

None of this was good for morale. Workers often look to management for reassurance but, in this case, management did not know the answers.

The GSC chose to dig deep in the face of challenge. It worked through those issues of morale, and soon learned that self-examination is a critical component in maintaining the momentum of culture change. Members of the GSC made that commitment to look in the mirror: to acknowledge areas of weakness and explore solutions.

In retrospect, perhaps Bernie and the Grassroots Committee were too hard on themselves. Often, as in this case, there are factors outside our control that play a pivotal role in the success or failure of any enterprise, especially one as unique as the Livermore Grassroots Safety Revolution.

Lesson Nine: Partnership and Perseverance

Every organization is challenged to meet business objectives while managing external demands. In difficult times, commitment often wains. But the Grassroots Safety Committee kept a cool head, sought assistance, and just stuck with the safety culture change process.

As a result of their rigorous self-examination, the GSC was able to take the steps necessary to rebuild and reinvent themselves. One of the most important steps they took was to partner with CCC to conduct a thorough safety culture assessment, to evaluate strengths and weakness, and develop an action plan for progress.

With the aid of objective, professional guidance, and with an abundance of grit, they successfully launched numerous initiatives. They involved supervisors and managers to a greater extent, in a way that was not threatening or critical, but supportive. They changed tacks to offer encouragement for near miss reporting and to steer clear of penalty or recrimination. Management became more involved again, and some managers served on the guidance team, to advise and assist rather than to manage the GSC. The GSC learned that rotating leadership periodically is essential to good health. The GSC was also divided into three more manageable groups, to reflect functional and geographic divisions which lead to more focused and relevant meetings. It also meant new leaders for what were now, not just one, but several grassroots committees. The GSC still exists and, true to its original structure, only hourly employees can be officers.

Bernie Mattimore is now retired. His charisma, wit and wisdom helped ignite a safety culture revolution that LLNL won’t soon forget. The current management team maintains the program and many of its original structures. And those nagging, lagging indicators also came back on track. Fifteen years after starting the grassroots safety culture at LLNL, the M&O department went a full year with only one lost workday injury.

As consultants who have dedicated more than 30 years to the science and practice of culture change, we have partnered with dozens of change champions. We have assessed hundreds of organizations in varying states of readiness. We have worked with naysayers. We have assisted thousands of guidance and grassroots team members. Each engagement with each client has informed our perspective and improved our practice. Taking part in the safety culture transformation at LLNL was profoundly rewarding. It was, and it remains, a shining example of what can happen when everything clicks. If you put expertise, trust, leadership and commitment in a bottle and shake it, you may just witness an explosion of excellence.

References

To view several additional items related to this article, visit www.asse.org/psextras.

Hogan, R. & Kaiser, R.B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 169-180.

Kotter, J.P. & Heskett, J.L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: The Free Press.

Ryan, K.K. & Oestreich, D.K. (1998). Driving fear out of the workplace: Creating the high-trust, high-performance organization (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schein, E.H. (1983, Summer). The role of the founder in the creation of organizational culture. Organizational Dynamics, 13-28.

Schein, E.H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schneider,W.E. (1995). Productivity improvement through cultural focus. Consulting Psychology: Practice and Research, 47(1), 3-27.

Simon, S.I. (1998). Safety culture assessment as a transformative process. Proceedings of the ASSE Behavioral Safety Symposium, USA, 192-207.

Simon, S.I. (2001). Implementing culture change: Three strategies. Proceedings of the 2001 Behavioral Safety Symposium: The Next Step, USA, 135-140.

Zohar, D. & Luria, G. (2005). Amultilevel model of safety climate: Cross-level relationship between organization and grouplevel climates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 616-628.