General Motors

Steve I. Simon, Ph.D.

President, CCC

Pat Frazee

Safety Director

During the early 1990s, General Motors was a beleaguered corporate giant battling a national economic downturn, global competition and conflict with its unions. Leadership was working overtime to set the company on a course that would allow it to regain lost ground in productivity, quality, market share and profitability. Help would come from an unlikely quarter— a companywide commitment to safety, specifically to the process of changing its safety culture. At that time, safety was somewhat of a foster child, considered separate from the company’s overall manufacturing culture. Its major unions, UAW and CAW, had been pressing the company to take safety more seriously. But now, some nine years after GM committed to a safety culture revolution, safety has been integrated into the larger cultural ethos. Working and working safely have become synonymous. Employee safety is accounted for in decision-making from design to production goals.

Safety has proven to be not only a natural rallying point for all stakeholders, but also a revolutionary anchor strategy for the entire company, catalyzing strides in employee-relations, quality and production. Championing a positive safety culture has boosted trust between worker and manager on a local level and between union and management globally. Safety culture change at GM was driven from the top and realized through the commitment and engagement of the leadership at every level. What follows is the story of how this was accomplished.

Top Leadership Initiatives

The Safety Report

Paul O’Neill, chair of Alcoa, joined the GM board of directors in 1993. His commitment to worker safety was key to the dramatic turnaround at Alcoa, where he not only improved safety, but also generated quantifiable bottom- line benefits. So perhaps GM’s directors should not have been surprised when, as they prepared to adjourn the first board meeting O’Neill attended, he asked, “Where’s the safety report?” There was none. O’Neill’s question—and its exposure of the status of safety at the company—would become a watershed moment in GM’s history. GM’s top brass could likely have glossed over O’Neill’s innocent question, or prepared a fancy report emphasizing the company’s efforts in safety and health and putting the best spin on their results. Instead, the President’s Council—the top seven executives at GM including CEO Jack Smith, Rick Wagoner and Harry Pearce—decided to meet the challenge and take a close look at GM’s safety performance and do whatever was necessary to improve it.

A Hard Look in the Mirror: The President’s Council

The President’s Council commissioned Harry Pearce, vice-chair of the board of directors, to spearhead the task. Pearce’s team took a hard look in the mirror and found that:

- Each year, nearly one of three GM workers was being injured seriously enough to require medical treatment.

- Nearly five percent of the workforce was being injured seriously enough to miss at least one day of work.

- GM was averaging about four occupational fatalities per year.

- Workers’ compensation costs exceeded $100 million annually.

Benchmarking

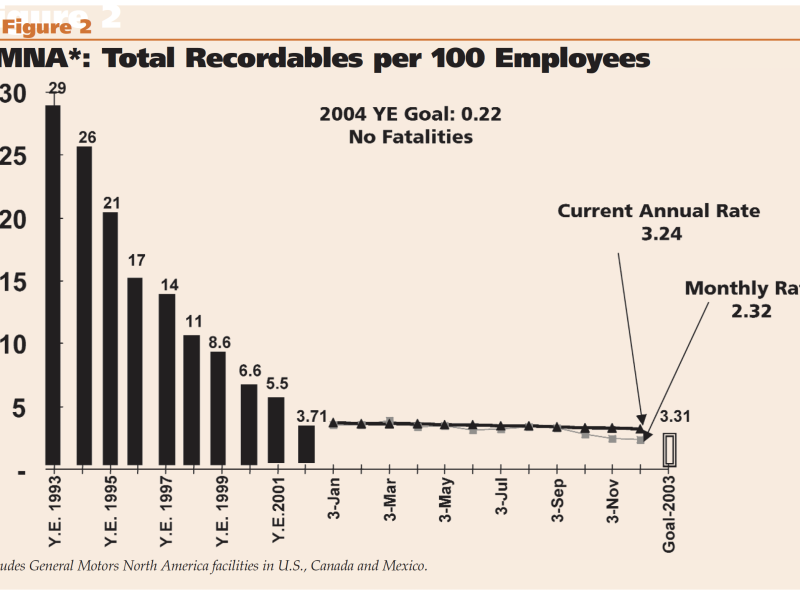

Clearly, it was time to light the safety lamp. Pearce’s team decided to benchmark the world’s best in safety and make some recommendations. That meant visits to companies such as Alcoa, DuPont and Allied Signal. The team discovered that GM was at least an order of magnitude behind these companies. For example, in 1993, the baseline used for all future measurements, GM’s total injury/illness incident rate in the U.S. was 29.5 per 100 employees; Alcoa’s was 2.7 and Dupont’s 0.6. Furthermore, GM’s lost workday case rate was 4.5 per 100 employees; Alcoa’s was 1.1 and Dupont’s 0.5. GM had not been neglecting its safety program over the previous two decades. In fact, the company had devoted a substantial amount of time, money and energy to safety and health. In 1973, the firm constituted a joint committee of company and union personnel to advance the cause. Safety specialists were employed at the plant level. GM was still allocating a nickel for every hour worked by every employee into a special safety and health budget, substantial amounts of which had been spent on materials and training. Despite these efforts, the company had made little headway in reducing injury and illness rates in recent years.

Why was it doing so badly?

It’s the Culture

Benchmarking results provided several clues. Until the President’s Council became involved, no common vision was in place and no imperative existed for top management to be involved in safety in a uniform way. As the O’Neill story showed, safety was not even an agenda item at top-level meetings. No central body planned long-range strategy for safety for the company. The firm had no corporate safety department and no corporate safety manager.

By contrast, GM representatives clearly saw that safety was the top priority with senior management at each of the benchmarked sites, setting the tone for the entire company. When a senior DuPont executive appeared at a plant site, the first point of discussion was safety. The plant’s safety statistics would be reviewed and if any kind of problem had been reported the senior executive would visit the location of the incident and talk to those involved.

The most telling insight came from an exchange between a GM host and an Alcoa observer on a reciprocal visit. Asked what he thought of GM’s safety and health offerings, the Alcoa expert remarked, “You have the best safety stuff I’ve ever seen on paper—four-color brochures and classy interactive training materials—but our guys never put their hands inside operating machines. We have the real safety thing. We have the culture.”

Pearce’s team acted fast and recommended a “culture focus,” a new approach for GM, to bring about long-term sustainable change in safety performance. If GM was going to operate its plants more safely, it had to change the culture—the way every layer of management and its employees looked at safety. But how is that accomplished at a company with 350,000 people working at 135 plants in 45 countries? By starting at the top.

Initiating Change

A Corporate Safety & Health Policy

Improving the safety culture was to become the key to making GM world-class in safety performance. Shortly after receiving the report and recommendations from Pearce’s team, the full President’s Council drafted a corporate safety and health policy: “We are committed to protecting the health and safety of each employee as the overriding priority of this corporation. There will be no compromise of an individual’s well-being in anything we do.” GM had espoused an official policy before, but never one authored and supported by its top leadership. In addition, the directors made perfectly clear where the ultimate responsibility resided:

“The implementation of actions to help our employees realize a healthy, injury-free environment is a leadership responsibility.”

A Bold Memorandum

The policy was presented to GM’s North American leadership in June 1994; it was also incorporated into a widely distributed memorandum that was to become a blueprint for implementing safety improvements over the next few years. This bold, three-page document, sent to executives and managers down to the plant level, is important in several ways.

On the first page, the President’s Council readily acknowledged the shortcomings of the company with regard to safety and health, and included the damaging comparisons to Alcoa and DuPont. Next, the council made clear that it will keep ownership and responsibility for safety. “The leadership of the President’s Council will be active and continuous. To keep the focus on an injury- and illness-free environment, safety is now one of our regular agenda items. We will review all fatalities and serious incidents promptly. In our everyday activities, we will ask the right questions [about safety], just as we now do about quality and cost.”

The leadership group also clearly specified aggressive safety and health goals where the President’s Council could and would be held accountable. “We have established an ambitious goal to reduce both the reportable incident rate and the lost workday case rate in the U.S. by 50 percent during the three-year period 1994 to 1996.”

Assigning Responsibility to the Manufacturing Leadership

The President’s Council mandated a radical shift with respect to implementing the new approach. Historically, responsibility for safety and health had belonged to GM’s personnel department. However, since 95 percent of all serious accidents occurred in the manufacturing process, the President’s Council declared that it was now to be “an operations responsibility which rests squarely with the leadership of each unit of General Motors.” Thus, the manufacturing heads of the 11 auto and truck divisions in North America, comprising the Manufacturing Managers’ Council (MMC) and overseeing 200,000 workers at 78 facilities and the production of 4.5 million vehicles, would now be accountable. The memo also discussed union involvement and measurement systems but returned forcefully to the issues of accountability and leadership. “We must hold ourselves accountable at all levels of management. Accordingly, an important element of every individual’s performance will be his or her attitude and demonstrated activities in promoting a healthy and injury-free environment.” While everyone in the company would be held responsible for his/her own attitudes and behavior, “continuous leadership involvement is the single most important factor for success.”

Channeling Change through the Divisions: MMC

The 11 members of MMC had received advanced copies of the benchmarking team’s report and the President Council’s memo announcing the new corporate safety and health policy. This group knew it would be their responsibility to turn GM’s safety performance around and to meet the ambitious goals of the President’s Council. These were people accustomed to responsibility, people who yearly, quarterly, monthly, even weekly, had to meet goals rarely known to be conservative. Now, these leaders were expected to treat safety just as they did cost and quality. Specifically, they had to meet two newly established safety goals—reducing lost-time and recordable injuries—and they had to determine how to accomplish these goals using the culture-focus methodology recommended by the benchmark team and endorsed by the President’s Council.

Understanding Safety Culture

Most members of MMC were unfamiliar with the concept of culture change as applied to safety, so they quickly began to educate themselves. For their monthly meeting in December 1994, they invited Dr. Steven Simon to make a presentation on “Achieving a World-Class Safety Culture.” Through this presentation, MMC learned how organizational culture is linked to safety and how it can be changed to improve and maintain safety performance.

What is safety culture? It is the sum of the underlying values, beliefs and assumptions that give every group and organization its unique identity. These can be positive, “I know that the people I work with will do nothing to jeopardize my safety,” or negative, “All management cares about is numbers, safety be damned.” Entrenched assumptions, whether accurate or inaccurate, influence the behavior and attitudes of group members. Once ingrained, culture is highly resistant to change.

Apositive safety culture cannot be bought; it is not a manual, a program, a video or a canned presentation. It requires the exercise of leadership at all levels and hard work over several years (at least five to seven) to be effective and lasting. By changing the culture in which management and workers operate, and influencing their behavior, a company has the potential to eliminate the greatest share of those accidents.

To understand how safety culture and safety programs interact, consider the analogy of a stew. The basic elements of a stew are the meat and vegetables, which may be paralleled to essential safety program elements such as training and equipment. The culture is the broth; no matter how excellent the meat and vegetables, no stew can survive a rancid broth. A positive culture, which is characterized by factors such as caring, leadership, trust, visibility and integrity, brings out the best in the safety program elements; a negative culture (a rancid broth) characterized by double standards, mistrust and focus on numbers instead of people poisons even the best safety program. GM may have had, as the Alcoa visitor observed, the very best safety program materials, but achieving its newly mandated goals would require equal dedication to creating a strong, positive safety culture.

Breaking Through: MMC’s Off-Site Meeting

MMC members asked what their first step should be and were told that a one-day off-site workshop would provide a good setting for these executives to look into their own mirror, examine their own behavior and test their personal attitudes toward safety. Before they could expect others to change, they would have to work on themselves.

The purpose of claiming a full day from these executives’ schedules was to begin to plan the cultural transformation needed to achieve the safety and health goals established by the President’s Council. MMC members invited their 34 divisional safety professionals to attend the meeting, but to preempt the appearance of a “hand-off” to the safety department, these professionals were strictly observers. The executives took ownership of the culture change process at this very first opportunity. During the morning session, several models that would be expected to play a major role in the diagnosis, design and implementation of the culture change plans were introduced. These required a shift from safety as the sum of policies, procedures and administrative programs toward a new paradigm demonstrating that safety performance is the product of culture, management and leadership processes no different than those at work in the other, more familiar arenas of effective organizational performance. The afternoon focused on tapping and unleashing the passion of the MMC members to lead their safety culture.

At first, they could not identify an external or internal driver that would sustain the requisite long-term effort, inspire them collectively and take them beyond rote compliance with mandates or even significant cost reduction. But when they “talked manufacturing,” they came alive. One MMC member spoke of having dreamed of making cars since he was five years old. He was still excited about his job, often unable to fall asleep with his head full of ideas for how to make better cars in a better way. He acknowledged that he was rarely preoccupied with safety concerns. However, he was not the only member to articulate that the discipline and attention to detail that go into manufacturing a car are the same discipline and attention that make for working safely. Problems in the area of safety are leading indicators of problems in other areas of manufacturing. Sloppiness in one area results in sloppiness in the other; cutting corners shows up in both.

Linking the safety culture with the manufacturing process was transformative. It engendered a significant breakthrough whereby MMC defined its role in safety as analogous to its leadership in pursuing the highest quality and care in the manufacture of cars and trucks.

“So What Are You Doing for Safety?”

The manufacturing executives could now truly begin to examine their own behavior. Each was asked to explain how he, individually, was exercising leadership on behalf of safety. The first volunteer began by talking about achievements in his division’s safety programs. “One thing we have done differently is to establish a new visitor protocol whereby people entering our plants are first oriented to the safety rules.” He was stopped and encouraged to speak in the first-person: “The question is what you, personally, are doing.” He began again. “One other thing I have done differently in my division is we have established a housekeeping program.”

“So a good safety effort is underway in your organization,” the consultant offered. “But what about your individual actions and contributions as a leader on behalf of safety? We know you have great programs, but they are not getting the job done. Cultures change through the actions of individual leaders. Transformational leadership is personal. It’s in your statements, questions, the items on your agendas, in the criteria you use to evaluate individuals and plants.”

Most participants agreed that they actually did not see themselves as leaders of safety. They relied on safety professionals for that. As one said, “When I call my five plant managers every Monday morning, I never ask about safety, about how many people got hurt. I ask about the number of cars they built last week and the quality measure on the rail head audit.” That is how both hourly and salaried employees had for years been receiving the message that it was okay to take shortcuts and risks for the sake of production. All agreed this had to change.

The support of one person in particular was considered crucial for the success of the fledgling culture change effort. Joe Spielman was chair of MMC and was considered a leader among leaders. He is respected equally by workers and management. Even today, Spielman recalls that meeting and the turning point. “As soon as we began to appreciate the link between what we were saying and doing and the safety culture of our plants, we knew we could and should be doing much more.”

Moving Forward

Managing a large-scale, long-term organizational culture change requires a dedicated infrastructure. It was recommended that MMC create a culture transition team to identify those activities that would best help them move forward. Accordingly, MMC chartered the first of what would become several transitional task forces.

Culture Transition Team I

The first Culture Transition Team (CTT I) was assembled in early 1995 under the leadership of Bud Darnell, a former plant manager assigned full time to the task. Mandated to report back to MMC at least once a month, CTT I was comprised of a representative mix of plant managers, safety professionals, engineers and human resources personnel. Union representation was built in from the onset. Mike Gracey, the union’s chief safety representative at the UAW-General Motors Center for Health and Safety, was invited to join the team as a founding member.

Bringing in the Union

During the early days of this effort, the benchmarking team asked the same question of each company and plant visited: “If you could do it (go through the process of establishing a safety culture) over again, would you do anything differently?” Without exception, all gave the same answer. They all said they would have involved their unions and employees in the process sooner.

GM had a solid structure for a joint effort. Management and the unions had been working together on safety and health for many years. The 1973 UAW-GM national agreement on safety and health was the first of its kind in the world. It had matured into a successful joint enterprise that had resulted in world-class training programs. As of 1993, however, the full, positive impact of these programs was still unrealized because of inconsistent and incomplete implementation.

MMC felt that union involvement in the new safety initiative would increase its chances for success. Furthermore, it might help heal the strain caused by the acrimonious and debilitating strikes of the early 1990s. At all levels, UAW had been pressing the company for full implementation of agreed-to programs and better safety practices for many years before this initiative. New leaders on both sides were determined to improve relations. This initiative provided an excellent opportunity to do just that—it offered a common goal that everyone could buy into. While union leaders expressed some justifiable skepticism, they agreed to participate.

Cutting through the Rhetoric

CTT I began by studying the Pearce team’s safety benchmarking report which declared that GM needed to make significant changes, especially in the area of leadership behavior. The company had often claimed that safety was its top priority, but that assertion did not stand up to scrutiny. In fact, the last employee survey conducted by human resources had revealed that GM workers did not believe the company’s rhetoric about safety. Now, after taking a concerted look in the mirror, even management was having its doubts.

During spring 1995, CTT I met twice a month, each time for three days, at different assembly plants, where their interviews and first-hand observations generated a new level of understanding of the status quo. Three members of the CTT I (team leader Darnell; director of safety for North American operations, Patrick Frazee; and Simon) briefed MMC monthly.

Working from the Top Down

For the first culture transition team, developing a long-term, all-encompassing safety plan would have been an unrealistic objective. One reason was the variety and complexity of plant operations—local labor conditions and agreements, vast differences in manufacturing processes, new product programs and GM’s massive reorganization efforts. The team also recognized that safety efforts would stall or, worse, be regarded by employees as more lip service unless and until top manufacturing executives were visibly perceived as leading the charge.

The trajectory for change at GM had always been top-down—senior leadership on board first, individual plant management next, then supervisory personnel and hourly workers. Accordingly, CTT I focused on launching the safety culture change process in the only forum that could make it work: they threw the ball back to MMC. The goal was to get top management to change its actions, attitudes and assumptions toward safety; to get visibly involved; and to engage the next level of management and so on down the pyramid, in keeping with the global GM culture.

“Going Common”

Specifically, CTT I proposed and MMC endorsed four initiatives through which MMC members could exercise and demonstrate their leadership. These were selected from dozens of ideas because they were highly visible, strongly symbolic and relatively easy to implement; furthermore, they would provide common ground for the safety culture initiative at all plants. This last attribute, “going common” (as it was known in the company), was an important GM concept based in manufacturing, where management always attempted to have all plants share the same values and language. MMC executives could and would engage their plant managers and employees in meaningful safety discussions around these four initiatives during every plant visit they made:

- Green Cross calendar program for reporting all serious accidents in every plant and in every department within the plant.

- Uniform injury/illness run chart tracking all recordable incidents, with pin map indicating the site of each.

- Universal plant visitors’ safety protocol.

- Two safety absolutes: “All accidents can be prevented” and “Safety is the overriding priority.”

Installing MMC’s Symbols

In August 1995, each GM plant in North America received a letter and a disk from MMC explaining what was happening and what was expected of them. While not every plant embraced the initiatives with alacrity, most installed the calendars, instituted the visitor protocol and adopted the uniform injury and illness measurements in a matter of months. Although the sheer size and diversity of the company guaranteed that some small percentage would lag behind, MMC’s demonstrated commitment to advancing culture change companywide provided strong motivation for plant managers to sign on. GM’s unions were delighted to see that they now shared a common commitment with the company’s top leaders.

It was evident that MMC was determined to win the safety war. The group was thinking and talking about it just as it did about car production. “We didn’t want this to be seen as just another program of the month, but a fundamental shift in our culture,” recalls MMC Chair Spielman. “We wanted every GM worker to be able to say honestly, ‘Yes, this is a company that really cares about my well-being.’”

At an MMC meeting shortly after the four initiatives were implemented, Spielman spoke of visiting a stamping plant where he observed a worker not wearing his elbow-length gloves. “I told the worker to put his gloves on and the worker said they didn’t have any. So I told him to go get some. He said it will take him 10 minutes to go to the storeroom and there is no one to replace him on the line. ‘Then we’ll have to shut down the line,’ I said. I could see he didn’t want to do it. ‘But Mr. Spielman, that will cost you 100 parts.’ ‘Go get the gloves!’ Believe me, I hated to lose those 100 parts, but I could see what an impression it made.”

Bowing Out

Just as CCT I had boldly recommended engaging senior leadership in the change process first, the team advocated that the approach which had worked for GM in building cars be adapted to identifying the next steps in building a positive safety culture. That meant engaging successive layers of management and employees, one at a time, slowly and in sequence. Any other approach would have gone against company structure, style and culture.

CTT I took one more action consistent with its insight and independence. Rather than hang on as a permanent planning group or as a staff group that saw itself as responsible for implementing the five- to seven-year culture change process, the team dissolved itself. It returned accountability to MMC and thereby emphasized the salience of the manufacturing executives’ continuing leadership. It recommended the appointment of a successor team dedicated to taking the culture change down through the ranks.

CTT II: Taking Culture Change to the Base of the Pyramid

CTT II included some CTT I members as well as new members. Like the first team, it was led by Bud Darnell. He, along with Frazee and Simon, continued to brief senior management monthly on progress. Encouraged by the results of CTT I, UAW also agreed to participate on this team.

CTT II assumed the challenge of drafting a blueprint for culture change that would cascade from plant leadership through supervision and ultimately to hourly workers. This blueprint would be structured in a recommendation asking MMC to authorize two separate safety leadership training courses: one for the plants’ top-tier managers and union officials (which was delivered during 1996-97 at 150 sites); and one for supervisors and union safety committee persons, conducted in the same plants for the next tier down a year or more after the top tier had started to apply the lessons of their training. Ajoint team consisting of UAW representatives and GM safety professionals participated in the development of both courses.

UAW leadership and MMC members quickly became advocates for the safety culture change approach. Leaders from both organizations spoke passionately at an 800-person meeting of the UAW-GM Joint Health and Safety Annual Conference, urging everyone to support the effort. The union and management safety leaders pledged their support.

Starting with Plant Leadership

In the context of the safety culture change process, plant leadership was defined as the plant manager, the human resources manager and two top union officials at each facility—dubbed the Key Four—plus area managers and department heads. MMC never moved out of the picture, however, even as managers at the plant level moved into CTT II’s sights. When MMC accepted CTT II’s recommendation and mandated a safety leadership course for plant personnel companywide, MMC members participated in each step— first by attending a four-hour executive overview of the training as a group, then attending the first of two eight-hour days with all plant leadership to consolidate their expectations in one room at one time.

MMC also took the lead in qualifying their respective plants for eligibility for the leadership training. “Exit criteria” (i.e., qualification) consisted principally of evidencing implementation of the first three MMC initiatives in the course of a facility tour and interviews conducted by divisional MMC member together with a union official.

The Plant Safety Leadership Course

The course itself is based on DuPont’s operations managers’ course and is adapted to a GM plant setting; it focuses on the identification (day one) and application (day two) at each site of four core components of a positive approach to safety—components that would become common to all GM sites. Aformer DuPont plant manager led each group through the establishment of four core components:

- A plant safety review board

- Incident investigation

- Safety audit and

- Safety contacts with employees

Safety leadership training emphasized the need to realize that it was possible to run an accident-free plant through caring about people, not just compliance. It was stressed that safety was to be management’s highest priority—above production, quality, cost and schedule. Leaders were expected to model behavior which showed that safety was their highest concern. They were to address unsafe acts or conditions immediately and, ultimately, they were responsible for the safety of themselves and those who worked for and around them

With the Key Four plus area managers and department heads in attendance, the application of the four core components to each plant could be tailored to its specific circumstances and culture. Involving plant management in the design and development of the new safety culture and how it would be applied to a given plant was by far the most important and far-reaching aspect of the two day plant management course. Getting input from instructors was valuable; having local leadership take ownership of the implementation was even more critical to its success.

Engaging Plant Supervisors & Union Committee Representatives

When it came to planning the safety leadership training course for the next tier—plant supervisors and union safety committee persons—CTT II recommended that joint in-house leadership (rather than outside professional trainers) should roll it out. That decision cemented the plant leadership’s stake in changing the safety culture; at the same time, it ensured credibility with the participants.

In cooperation with CTT II, the Joint UAW/GM Center for Health and Safety prepared accompanying materials. Over a two-year period, local plant managers conducted the supervisors/committeepersons safety leadership course at every GM plant in North America. The course had four modules that overlapped with the components of the plant safety leadership course: 1) plant safety review board, 2) safe operating practices, 3) incident investigation and 4) safety observation tours. To this day, any new supervisor who joins GM must attend one of the periodic courses that are designed to promote common language and values throughout the company.

With the implementation of CTT II’s educational action plans to extend the personal investments of GM’s 11 top manufacturing managers (MMC) in the policy of spearheading culture change by making safety an overriding corporate priority, the process was launched. Local plant leaders were driving safety down through the hierarchy in their own plants; supervisors and union committee representatives were listening to and responding to worker concerns. By now, the culture change had reached the plant floor. The following describes what it looked like from the perspective of a single assembly plant.

Snapshot: The Fairfax Story

The Fairfax Assembly Plant in Kansas City, KS, has been in operation since the 1940s, although a completely new facility opened in 1987. Dwayne Dunsmore, Fairfax’s veteran safety professional, was a member of CTT I.

Dunsmore recalls working three days a week for months on CTT, first reviewing the initial benchmarking, then visiting plants (GM’s as well as others) and finally creating a report to present to MMC. “It was a pretty intense effort,” he says. “The committee was a cross-section of GM—people from corporate, manufacturing, union, and health and safety. Most members knew little or nothing about culture change when we started.”

To qualify for the safety leadership training, Fairfax, like every other site, not only had to adopt MMC’s initiatives, it also had to design a detailed rollout plan that articulated the number, size and timetable for training sessions. Furthermore, the site had to demonstrate real buy-in by plant personnel, both salaried and hourly. To that end, all employees completed questionnaires asking whether they favored the new joint safety culture change project and whether they would give it their full support.

According to Al Neal, safety and health representative for UAW Local 31 for many years, who was Dwayne Dunsmore’s union counterpart, it was not the easiest sell. “Union membership was leery. Would management continue its support or would this become another flavor of the month? Since labor was being asked to partner in the program, would the union be blamed for failures?” Positive elements were noted, such as the chance to have more input into safety and the promise of faster response to maintenance requests. But the deciding factor seems to have been the endorsement of the top brass of both the company and union. “That carried a lot of weight,” says Neal. “Still, we had a wait-and-see attitude about whether they would carry through on their promises.”

They did. The first people at Fairfax to complete the two-day plant safety leadership course were the Key Four, area managers and the union’s safety and health representatives. Both Dunsmore and Neal say it was essential that the course for the next tier—supervisor/ committeeperson safety leadership course— was introduced by the plant manager and union chair in tandem. “Having them both out front together sent a powerful message,” according to Neal. “Then when they actually began to lead some of the training based on what they had previously learned, it certainly added to the credibility of the program.” Area managers also led training sessions, along with the safety and health officers. In all, more than 200 people participated in the Fairfax safety culture courses.

“Management involvement was more than symbolic,” says Dunsmore. “Previously, safety was seen primarily as the province of the safety professional. . . . But all that changed once MMC and plant management stood up and said, ‘We are all responsible for safety and we will all be held accountable.’ Suddenly everyone began to focus on safety. It became much, much easier to get things done. And they have kept the heat turned up. MMC now shows up every year at the annual joint safety training conference. Plant managers are rated for the safety performance of their plants and safety is used as an evaluation tool for everyone in the organization.”

The Daily Safety Walk

The safety observation tour (the daily safety walk) has become the main vehicle of safety culture change at Fairfax. Shortly after each shift starts, the plant manager, his staff, union leaders and joint safety and health representatives take up to 45 minutes to tour one department with the area manager and superintendents. Each day they tour another area. They have been doing this consistently for eight years, talking to plant personnel and looking for unsafe conditions and behaviors, as well as keeping an eye out for best practices. Every problem they encounter is assigned for resolution. Each department has it own tracking system and the following week the superintendent must report on any open items. This list is kept active and online where it can be reviewed regularly.

Neal notes a change in how the list is handled. “At first, we were overwhelmed and all we could focus on were the most serious problems. Now, while we still throw most of our resources at those, we are in a better position to knock off the little stuff, the water drip that is driving somebody crazy, repainting the lines that have become all but invisible. If you let these things go for months, somebody’s going to be disappointed. We find that when you take care of the little problems that are bothering people, they are much more likely to go the extra mile for you.”

One danger he noticed was the tendency to want to bring out other issues during these tours. “From time to time, both managers and workers have brought up extraneous issues and grievances. What we try to do is keep everyone focused on safety.” Serious incidents and near-hits identified during the daily walk are referred for audit. Fairfax has further refined the process to include an audit of near-near hits, which enables those involved to report on any potential, possible incident. Each department’s standard operating procedures are also audited to make sure they contain sufficient detail. These must measure up to a simple standard, defined by Dunsmore as “what you would tell your wife, husband or child if they were coming to work in the department, in order to keep them safe.”

At the end of each tour, the day’s findings are reviewed—with positive feedback delivered first. “You can’t just keep beating people down,” says Dunsmore. “And usually there is a lot more being done right than wrong.”

The spirit of cooperation and mutual respect has developed over the years, centered largely on these observation tours. “I come from the grievance side,” says Neal. “It used to be that you would spot a problem, file a grievance and ask questions later. Now, 90 to 95 percent of all problems are handled by first talking about them and solving them. When you are confident in the good faith of other parties, it makes things much easier.”

Dividens

Success has also fueled the culture change process at Fairfax. As incident rates have declined, faith in the system has increased. The site has reported nearly continuous improvement for nine years. In 1994, the year before the change effort began, Fairfax’s annual recordable rate was 33.5; in 2003, it was down to 5.02—an 85-percent reduction. During the same period, the lost workday case rate was reduced from more than 3.5 to less than 0.5, another 85-percent reduction.

Management’s unswerving support is critical. “At first, we wondered if they would walk the talk,” says Neal. “They have certainly done that. And it’s not just one or two individuals leading the charge. Over the years, there have been changes on the board, on MMC; we have changed plant managers and it just keeps going and growing. Now, it’s no longer about individual heroics, it’s about the culture.”

The positive safety culture appears to have benefits in other areas as well. Morale on the shopfloor is appreciably higher, union and management relations have never been better and more work gets done because, if nothing else, fewer people are out with illnesses or injuries. “We still have our own agendas,” says Neal, “but we realize there is a lot of common ground. Now, when we disagree on something, we are much more likely to go off and discuss it.”

Dunsmore is understandably proud of having participated in the program and having promoted a more positive safety culture. “It’s very satisfying to have seen these changes take hold and to know I’m leaving behind a safer place to work.”

Reaching the Shopfloor

The saying at GM (and probably a lot of other places) is that “employees don’t care what you know until they know that you care.” In many ways, that sums up how this particular safety culture initiative succeeded at the Fairfax Assembly Plant as well as at dozens of other GM manufacturing facilities. No amount of expertise will change the way people worked, unless that expertise is accompanied by engagement and led from the top. At GM, only when managers and supervisors across the board began to talk aggressively to workers about their concerns, investigate incidents with the intention of correcting underlying root causes and demonstrate how important they felt worker safety was, did workers truly begin to heed their directives. By increasing the points of contact, communication improved dramatically.

As the culture changed, workers began to stop putting their hands in machines. Workers do not hurt themselves deliberately, but they can and sometimes do expose themselves to unnecessary risks. Statistics showed that 80 percent of all serious accidents at GM occurred among the skilled trades, not on the assembly line. These workers set up and repair equipment, and troubleshoot problems. This is non repetitive work and these workers make many choices each day regarding how to proceed. Often, the choice had been between speed and care. As the message about safety reached them—repeatedly—they began to take better care of themselves; soon, the number of serious accidents started to drop—then dropped even more.

Safety works wonders as an anchor strategy: Improve safety and quality, production and better employee relations will follow. This improved trust between worker and manager, fueled largely by having safety concerns addressed, has been invaluable in sustaining the downward trend of injuries at GM over nine successive years. Without the buy-in and participation of hourly employees, continued gains would have been impossible. Leadership commitment was the first driver at GM, but it is workers’ enlightened self-interest that has kept the process rolling.

What has continued to drive it? In the beginning, it was certainly top leadership’s fervent commitment. The same competitive spirit that has catalyzed GM’s manufacturing initiatives was harnessed as determination to surpass those companies GM once benchmarked itself against. Early successes encouraged the troops. Setting and meeting interim targets is an excellent way to motivate people and measure progress; the fact that the company met its ambitious injury reduction goals certainly helped spur further efforts.

Conclusion

GM used to begin its safety leadership training course by asking participants where they would prefer to have their children work, at GM or in the coal mines. The response was invariably GM. Then the trainer would report that it was actually safer to work in a coal mine than in a GM assembly plant. That fact no longer holds true. Once the safety car started rolling at GM, it picked up momentum. The company and its unions have seen nine straight years of continuous improvement, and safety performance numbers today rival and in some cases surpass those of the great companies that were benchmarked in 1994.

In a quick-fix, instantaneous-results business world, where the next 90-day report to the analysts dictates how operations are run, the largest company in the world made a decade-long commitment to change its safety culture. As a result, management and employees now work with a common purpose toward a common goal—to deliver the vehicles they produce in an accident-free environment.

References

To view several additional items related to this article, visit www.asse.org/psextras.

Hogan, R. & Kaiser, R.B. (2005). What we know about leadership. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 169-180.

Kotter, J.P. & Heskett, J.L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. New York: The Free Press.

Ryan, K.K. & Oestreich, D.K. (1998). Driving fear out of the workplace: Creating the high-trust, high-performance organization (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schein, E.H. (1983, Summer). The role of the founder in the creation of organizational culture. Organizational Dynamics, 13-28.

Schein, E.H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Schneider,W.E. (1995). Productivity improvement through cultural focus. Consulting Psychology: Practice and Research, 47(1), 3-27.

Simon, S.I. (1998). Safety culture assessment as a transformative process. Proceedings of the ASSE Behavioral Safety Symposium, USA, 192-207.

Simon, S.I. (2001). Implementing culture change: Three strategies. Proceedings of the 2001 Behavioral Safety Symposium: The Next Step, USA, 135-140.

Zohar, D. & Luria, G. (2005). Amultilevel model of safety climate: Cross-level relationship between organization and grouplevel climates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 616-628.